King Humbert I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Umberto I ( it, Umberto Rainerio Carlo Emanuele Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Eugenio di Savoia; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with

Despite the defeat at Adwa, Umberto still harbored imperialistic ambitions towards Ethiopia, saying: "I am what they call a warmonger and my personal wish would be to strike back at Menelik and avenge our defeat." In 1897, the prime minister,

Despite the defeat at Adwa, Umberto still harbored imperialistic ambitions towards Ethiopia, saying: "I am what they call a warmonger and my personal wish would be to strike back at Menelik and avenge our defeat." In 1897, the prime minister,

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil ''belle époque''. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil ''belle époque''. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the

p. 47

/ref> * Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, ''30 January 1859''; Grand Master, ''9 January 1878'' *

(in Italian), ''Il sito ufficiale della Presidenza della Repubblica''. Retrieved 2018-08-14. * Grand Master of the

External link: Genealogy of recent members of the House of Savoy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Umberto 01 Of Italy 1844 births 1900 deaths 1900 murders in Italy 19th-century kings of Italy 19th-century kings of Sardinia 19th-century murdered monarchs Nobility from Turin Italian monarchs Italian princes Roman Catholic monarchs Princes of Savoy Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class) Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece of Austria Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary 3 3 3 Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand Italian people of Polish descent Claimant Kings of Jerusalem Deaths by firearm in Italy Male murder victims Kings of Italy (1861–1946) Grand Masters of the Gold Medal of Military Valor Burials at the Pantheon, Rome Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader, ...

from 9 January 1878 until his assassination on 29 July 1900.

Umberto's reign saw Italy attempt colonial expansion into the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

, successfully gaining Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

and Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

despite being defeated by Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

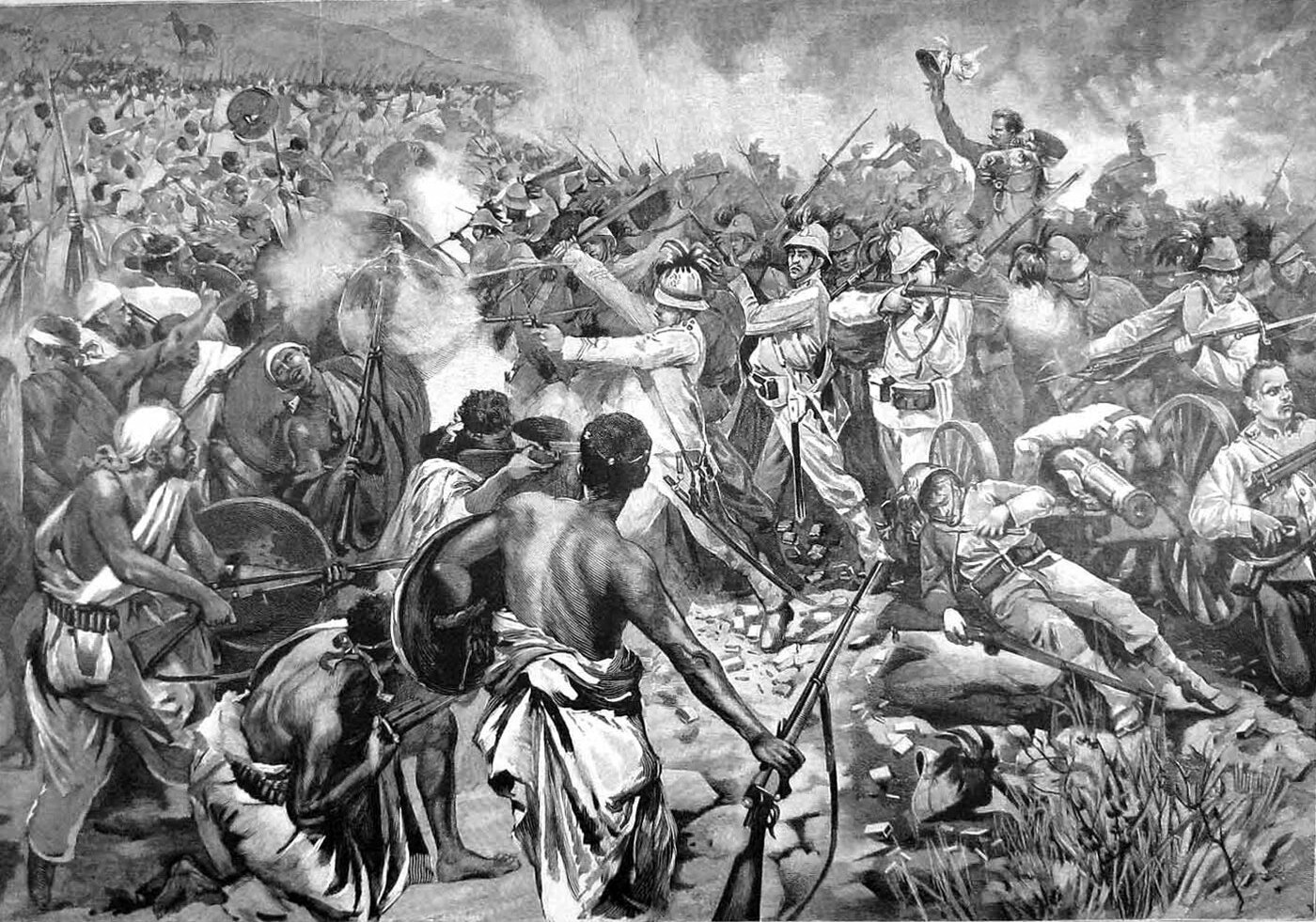

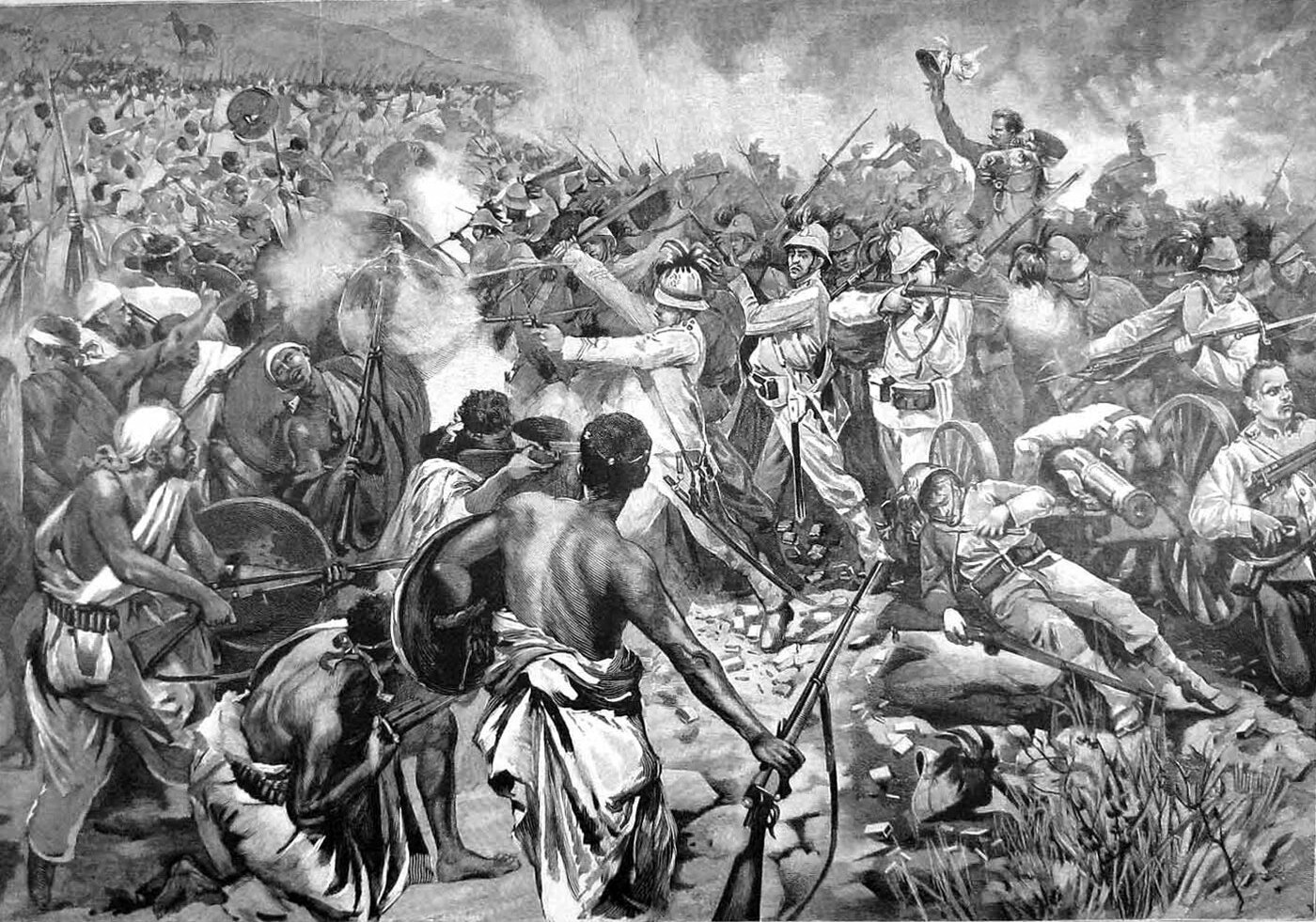

at the Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The de ...

in 1896. In 1882, he approved the Triple Alliance with the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

He was deeply loathed in leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

circles for his conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

and support of the Bava Beccaris massacre

The Bava Beccaris massacre, named after the Italian General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris, was the repression of widespread food riots in Milan, Italy, on 6–10 May 1898. In Italy the suppression of these demonstrations is also known as ''Fatti di Magg ...

in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. He was especially hated by anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, who attempted to assassinate him during the first year of his reign. He was killed by another anarchist, Gaetano Bresci

Gaetano Bresci (; November 10, 1869May 22, 1901) was an Italian-American anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I of Italy on July 29, 1900. Bresci was the first European regicide not to be executed, as capital punishment in Italy had been a ...

, two years after the Bava Beccaris massacre.

Youth

The son ofVictor Emmanuel II

Victor Emmanuel II ( it, Vittorio Emanuele II; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia from 1849 until 17 March 1861, when he assumed the title o ...

and Archduchess Adelaide of Austria, Umberto was born in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, which was then capital of The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, on 14 March 1844, his father's 24th birthday. His education was entrusted to, among others, Massimo Taparelli, Marquess d'Azeglio, and Pasquale Stanislao Mancini

Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, 8th Marquess of Fusignano (17 March 1817 – 26 December 1888) was an Italian jurist and statesman.

Early life

Mancini was born in Castel Baronia, in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (present-day Province of A ...

. As Crown Prince, Umberto was distrusted by his father, who gave him no training in politics or constitutional government, and he was brought up with no affection or love. Instead, Umberto was taught to be obedient and loyal; had to stand at attention whenever his father entered the room; and when speaking to his father had to get down on his knees to kiss his hand first. The fact that Umberto had to kiss his father's hand before being allowed to speak to him both in public and in private right up to his father's death contributed much to the tension between the two.

From March 1858, he had a military career in the Royal Sardinian Army

The Royal Sardinian Army (also the Sardinian Army, the Royal Sardo-Piedmontese Army, the Savoyard Army, or the Piedmontese Army) was the army of the Duchy of Savoy and then of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was active from 1416 until it became th ...

, beginning with the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. Umberto took part in the Italian Wars of Independence The War of Italian Independence, or Italian Wars of Independence, include:

* First Italian War of Independence (1848–1849)

*Second Italian War of Independence (1859)

*Third Italian War of Independence (1866)

* Fourth Italian War of Independence ( ...

: he was present at the battle of Solferino

The Battle of Solferino (referred to in Italy as the Battle of Solferino and San Martino) on 24 June 1859 resulted in the victory of the allied French Army under Napoleon III and Piedmont-Sardinian Army under Victor Emmanuel II (together known ...

in 1859, and in 1866 commanded the XVI Division at the Villafranca battle that followed the Italian defeat at Custoza.

Because of the upheaval the Savoys caused to a number of other royal houses (all the Italian ones, and those related closely to them, such as the Bourbons of Spain and France) in 1859–60, only a minority of royal families in the 1860s were willing to establish relations with the newly founded Italian royal family. It proved difficult to find any royal bride for either of the sons of king Victor Emmanuel II (his younger son Amedeo, Umberto's brother, married ultimately a Piedmontese subject, princess Vittoria of Cisterna). Their conflict with the papacy did not help these matters. Not many eligible Catholic royal brides were easily available for young Umberto.

At first, Umberto was to marry Archduchess Mathilde of Austria, a scion of a remote sideline of the Austrian imperial house; however, she died as the result of an accident at the age of 18. On 21 April 1868, Umberto married his first cousin, Margherita Teresa Giovanna, Princess of Savoy

Margherita of Savoy (''Margherita Maria Teresa Giovanna''; 20 November 1851 – 4 January 1926) was Queen of Italy by marriage to Umberto I.

Life

Early life

Margherita was born to Prince Ferdinand of Savoy, Duke of Genoa and Princess Elisabeth ...

. Their only son was Victor Emmanuel, prince of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. While Umberto was to be described by a modern historian as "a colorless and physically unimpressive man, of limited intellect" Margherita's appearance, cultural interests and strong personality were to enhance the popularity of the monarchy. Umberto kept many mistresses on the side, and his favorite mistress, Eugenia, the wife of Duke Litta Visconti-Arese, lived with him at his court as his common-law wife as he forced Queen Margherita to accept her as a lady-in-waiting.

In 1876, when the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Salisbury, visited Rome, he reported to London that King Victor Emmanuel II and Crown Prince Umberto were "at war with each other". Upon taking the Crown, Umberto dismissed all of his father's friends from the court, sold off his father's racing horse collection (which numbered 1,000 horses) and cut down on extravagances to pay down the debts Victor Emmanuel II had run up. The British historian Denis Mack Smith

Denis Mack Smith CBE FBA FRSL (3 March 1920 – 11 July 2017) was an English historian who specialized in the history of Italy from the Risorgimento onwards. He is best known for his biographies of Garibaldi, Cavour and Mussolini, and for hi ...

commented that it was sign of the great wealth of the House of Savoy that Umberto was able to pay off his father's debts without having to ask parliament for assistance. Like his father, Umberto was a poorly educated man without intellectual or artistic interests, never read any books, and preferred to dictate rather than write letters as he found writing to be too mentally taxing. After meeting him, Queen Victoria described Umberto as having his father's "gruff, abrupt manner of speaking", but without his "rough speech and manners". In contrast, Queen Margherita was widely read in all the classics of European literature, kept up a salon of intellectuals, and despite the fact that French was her first language was often praised for her beautiful Italian in her letters and when speaking.

Reign

Accession to the throne and first assassination attempt

Ascending the throne on the death of his father (9 January 1878), Umberto adopted the title "Umberto I of Italy" rather than "Umberto IV" (of Savoy), and consented that the remains of his father should be interred at Rome in thePantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

, rather than the royal mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

of Basilica of Superga

The Basilica of Superga () is a church in Superga, in the vicinity of Turin.

History

It was built from 1717 to 1731 for Victor Amadeus II of Savoy, designed by Filippo Juvarra, at the top of the hill of Superga. This fulfilled a vow the duke ...

. While on a tour of the kingdom, accompanied by Queen Margherita and the Prime Minister Benedetto Cairoli

Benedetto Cairoli (28 January 1825 – 8 August 1889) was an Italian politician.

Biography

Cairoli was born at Pavia, Lombardy. From 1848 until the completion of Italian unity in 1870, his whole activity was devoted to the ''Risorgimento'', as ...

, he was attacked with a dagger by an anarchist, Giovanni Passannante

Giovanni Passannante (; February 19, 1849 – February 14, 1910) was an Italian anarchist who attempted to assassinate king Umberto I of Italy, the first attempt against Savoy monarchy since its origins. Originally condemned to death, his sentence ...

, during a parade in Naples on 17 November 1878. The King warded off the blow with his sabre, but Cairoli, in attempting to defend him, was severely wounded in the thigh. The would-be assassin was condemned to death

''Condemned to Death'' is a 1932 British crime film directed by Walter Forde and starring Arthur Wontner, Gillian Lind and Gordon Harker. It was adapted from the play ''Jack O'Lantern'' by James Dawson which was itself based on a 1929 novel by ...

, even though the law only allowed the death penalty if the King was killed. The King commuted the sentence to one of penal servitude for life, which was served in a cell only high, without sanitation and with of chains. Passanante would die three decades later in a psychiatric institution.

Foreign policy

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, repeatedly visiting Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. Many in Italy, however, viewed with hostility an alliance with their former Austrian enemies, who were still occupying areas claimed by Italy. A strong militarist, Umberto loved Prussian-German militarism and on his visits to Germany his favorite activity was to review the Prussian Army and he was greatly honored to be allowed to lead a Prussian hussar regiment on field maneuvers outside of Frankfurt. Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany told him during one visit that he should strengthen the ''Regio Esercito'' to the point that he could abolish parliament and rule Italy as a dictator.

A major criticism of the policies carried out by the Prime Ministers appointed by Umberto was the continued power of organized crime in the ''Mezzogiorno'' (southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

) with the Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

dominating Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and the Camorra dominating Campania

Campania (, also , , , ) is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islands and the i ...

. Both the Mafia and the Camorra functioned as "parallel states" whose existence and power was tolerated by successive governments in Rome as both the Mafia and the Camorra engaged in electoral fraud and voter intimidation so effective that it was Mafia and Camorra bosses who decided who won elections. As it was impossible to win elections in the ''Mezzogiorno'' without the support of organized crime, politicians cut deals with the bosses of the Camorra and Mafia to exchange toleration of their criminal activities for votes. The ''Mezzogiorno'' was the most backward region of Italy with high levels of poverty, emigration and an illiteracy rate estimated as high as 70%. The deputies from the ''Mezzogiorno'' always voted against more schools for the ''Mezzogiorno'', thus perpetuating southern backwardness and poverty as both the Mafia and the Camorra were opposed to any sort of social reform that might threaten their power. However, the king preferred heavy military spending rather than engaging in social reforms and every year, the Italian state spent 10 times more money on the military than on education. Umberto, an aggressive proponent of militarism, once said that to accept cuts in the military budget would be "an abject scandal and we might as well give up politics altogether". At least part of the reason why Umberto was so opposed to cutting the military budget was because he personally promised Emperor Wilhelm II that Italy would send 5 army corps to Germany in the event of a war with France, a promise that the king did not see fit to share with his prime ministers.

Umberto was also favorably disposed towards the policy of colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

expansion inaugurated in 1885 by the occupation of Massawa in Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

. Italy expanded into Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

in the 1880s as well. Umberto's preferred solution to the problems of Italy was to conquer Ethiopia, regardless of overwhelming public opposition, and supported the ultra-imperialist Prime Minister Francesco Crispi

Francesco Crispi (4 October 1818 – 11 August 1901) was an Italian patriot and statesman. He was among the main protagonists of the Risorgimento, a close friend and supporter of Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, and one of the architect ...

who in May 1895 spoke of "the absolute impossibility of continuing to govern through Parliament." In December 1893, Umberto appointed Crispi prime minister despite his "shattered reputation" due to his involvement in the Banca Romana scandal

The ''Banca Romana'' scandal surfaced in January 1893 in Italy over the bankruptcy of the ''Banca Romana'', one of the six national banks authorised at the time to issue currency. The scandal was the first of many Italian corruption scandals, and ...

together with numerous other scandals that the king himself called "sordid". As Crispi was heavily in debt, the king secretly agreed to pay off his debts in exchange for Crispi following the king's advice.

Umberto openly called Parliament a "bad joke" and refused to allow Parliament to meet again lest Crispi faced difficult questions about the Banca Romana scandal. Crispi only avoided indictment because of his parliamentary immunity. When the king was warned that it was dangerous for the crown to support someone like Crispi, Umberto replied that "Crispi is a pig, but a necessary pig", who despite his corruption, had to stay in power for "the national interest, which is the only thing that matters". With the support of the king, Crispi governed in an authoritarian manner, preferring to pass legislation by having the king issue royal decrees as opposed to getting bills passed by Parliament. On 25 June 1895 Crispi refused to allow a parliamentary inquiry into the bank scandal, saying as a prime minister he was above the law because he had "served Italy for 53 years". Umberto I was suspected of aspiring to a vast empire in north-east Africa, a suspicion which tended somewhat to diminish his popularity after the disastrous Battle of Adwa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The de ...

in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

on 1 March 1896. After the Battle of Adwa, public frustration with the deeply unpopular war with Ethiopia came to the fore, and demonstrations broke out in Rome with people shouting "death to the king!" and "long live the republic!".

Despite the defeat at Adwa, Umberto still harbored imperialistic ambitions towards Ethiopia, saying: "I am what they call a warmonger and my personal wish would be to strike back at Menelik and avenge our defeat." In 1897, the prime minister,

Despite the defeat at Adwa, Umberto still harbored imperialistic ambitions towards Ethiopia, saying: "I am what they call a warmonger and my personal wish would be to strike back at Menelik and avenge our defeat." In 1897, the prime minister, Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì

Antonio Starrabba (o Starabba), Marquess of Rudinì (16 April 18397 August 1908) was an Italian statesman, Prime Minister of Italy between 1891 and 1892 and from 1896 until 1898.

Biography Early life and patriotic activities

He was born in Pal ...

tried to sell Eritrea to Belgium on the grounds that Eritrea was too expensive to hold onto, but was overruled by the king who insisted that Eritrea must stay Italian. Rudinì attempted to reduce military spending, citing a study showing that since 1861 military spending constituted over half the budget every year, but was again blocked by the king. In 1899, Foreign Minister Felice Napoleone Canevaro dispatched a ''Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the Italian constitutional referendum, 1946, birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' ch ...

'' squadron to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

with an ultimatum demanding that the Chinese government

The Government of the People's Republic of China () is an authoritarian political system in the People's Republic of China under the exclusive political leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It consists of legislative, executive, mili ...

hand over a coastal city to be ruled as an Italian concession

Concession may refer to:

General

* Concession (contract) (sometimes called a concession agreement), a contractual right to carry on a certain kind of business or activity in an area, such as to explore or develop its natural resources or to opera ...

in the same manner as other Western imperial powers in China. Prime Minister Luigi Pelloux

Luigi Gerolamo Pelloux ( La Roche-sur-Foron, 1 March 1839 – Bordighera, 26 October 1924) was an Italian general and politician, born of parents who retained their Italian nationality when Savoy was annexed to France. He was the Prime Minister o ...

and his fellow cabinet ministers stated that Canevaro had acted without informing them, and it was widely believed that the king was the one who given Canevaro the orders to acquire a concession in China. After the Chinese government refused, Canevaro threatened war, but was forced to back down and settled for breaking diplomatic relations with China.

In the summer of 1900, Italian forces were part of the Eight-Nation Alliance

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, then besieged by the popular Boxer militia, who were determined to remove fo ...

which participated in the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

in Imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

. Through the Boxer Protocol, signed after Umberto's death, the Kingdom of Italy gained a concession territory

In international relations, a concession is a " synallagmatic act by which a State transfers the exercise of rights or functions proper to itself to a foreign private test which, in turn, participates in the performance of public functions and th ...

in Tientsin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

.

Umberto's attitude towards the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

was uncompromising. In an 1886 telegram, he declared Rome "untouchable" and affirmed the permanence of the Italian possession of the "Eternal City".

Turmoil

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil ''belle époque''. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil ''belle époque''. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and a ...

, the spread of socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

ideas, public hostility to the colonialist

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

plans of the various governments, especially Crispi's, and the numerous crackdowns on civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

. The protesters included the young Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, then a member of the socialist party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of t ...

. On 22 April 1897, Umberto I was attacked again, by an unemployed ironsmith, Pietro Acciarito, who tried to stab him near Rome.

Bava Beccaris massacre

During the colonial wars in Africa, large demonstrations over the rising price of bread were held in Italy and on 7 May 1898, the city ofMilan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

was put under military rule by General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris (; 17 March 1831 – 8 April 1924) was an Italian general, especially remembered for his brutal repression of riots in Milan in 1898, known as the Bava Beccaris massacre.

Biography

Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris was born in Fossa ...

, who ordered rifle-fire and artillery against the demonstrators. As a result, 82 people were killed according to the authorities, with opposition sources claiming that the death toll was 400 dead with 2,000 wounded. King Umberto sent a telegram to congratulate Bava Beccaris on the restoration of order and later decorated him with the medal of Great Official of Savoy Military Order, greatly outraging a large part of the public opinion

Public opinion is the collective opinion on a specific topic or voting intention relevant to a society. It is the people's views on matters affecting them.

Etymology

The term "public opinion" was derived from the French ', which was first use ...

.

Assassination

On the evening of 29 July 1900, Umberto was assassinated inMonza

Monza (, ; lmo, label=Lombard language, Lombard, Monça, locally ; lat, Modoetia) is a city and ''comune'' on the River Lambro, a tributary of the Po River, Po in the Lombardy region of Italy, about north-northeast of Milan. It is the capit ...

. The king was shot four times by the Italian-American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, w ...

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

Gaetano Bresci

Gaetano Bresci (; November 10, 1869May 22, 1901) was an Italian-American anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I of Italy on July 29, 1900. Bresci was the first European regicide not to be executed, as capital punishment in Italy had been a ...

. Bresci claimed he wanted to avenge the people killed in Milan during the suppression of the riots of May 1898.

Umberto was buried in the Pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone S ...

in Rome, by the side of his father Victor Emmanuel II, on 9 August 1900. He was the last Savoy to be buried there, as his son and successor Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

died in exile and was buried in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

until his remains were transferred to Vicoforte

Vicoforte is a ''comune'' in the Province of Cuneo in Italy. It is located in Val Corsaglia at above sea level, east of Cuneo and from Mondovì.

It is known mainly for the Santuario di Vicoforte, built between 1596 and 1733 to honour the Virgin ...

near Cuneo

Cuneo (; pms, Coni ; oc, Coni/Couni ; french: Coni ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Northern Italy, the capital of the province of Cuneo, the fourth largest of Italy’s provinces by area.

It is located at 550 metres (1,804 ft) in ...

in 2017.

American anarchist Leon F. Czolgosz

Leon Frank Czolgosz ( , ; May 5, 1873 – October 29, 1901) was an American laborer and anarchist who assassinated President William McKinley on September 6, 1901, in Buffalo, New York. The president died on September 14 after his wound became ...

claimed that the assassination of Umberto I was his inspiration to kill President William McKinley in September 1901.

Honours

Italian

* Knight of the Annunciation, ''30 January 1859''; Grand Master, ''9 January 1878''Justus Perthes, ''Almanach de Gotha'' (1900p. 47

/ref> * Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, ''30 January 1859''; Grand Master, ''9 January 1878'' *

Gold Medal of Military Valour

The Gold Medal of Military Valour ( it, Medaglia d'oro al valor militare) is an Italian medal established on 21 May 1793 by King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia for deeds of outstanding gallantry in war by junior officers and soldiers.

The fac ...

, ''1866''"Umberto Ranieri di Savoia"(in Italian), ''Il sito ufficiale della Presidenza della Repubblica''. Retrieved 2018-08-14. * Grand Master of the

Military Order of Savoy

The Military Order of Savoy was a military honorary order of the Kingdom of Sardinia first, and of the Kingdom of Italy later. Following the abolition of the Italian monarchy, the order became the Military Order of Italy.

History

The origin o ...

* Grand Master of the Order of the Crown of Italy

The Order of the Crown of Italy ( it, Ordine della Corona d'Italia, italic=no or OCI) was founded as a national order in 1868 by King Vittorio Emanuele II, to commemorate the unification of Italy in 1861. It was awarded in five degrees for civi ...

* Grand Master of the Civil Order of Savoy

* Commemorative Medal of Campaigns of Independence Wars

* Commemorative Medal of the Unity of Italy

The Italian Risorgimento was celebrated by a series of medals set up by the three kings who ruled during the long process of unification - the Commemorative Medal for the Campaigns of the War of Independence and the various versions of the Commemor ...

Foreign

Ancestry

References

External links

External link: Genealogy of recent members of the House of Savoy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Umberto 01 Of Italy 1844 births 1900 deaths 1900 murders in Italy 19th-century kings of Italy 19th-century kings of Sardinia 19th-century murdered monarchs Nobility from Turin Italian monarchs Italian princes Roman Catholic monarchs Princes of Savoy Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class) Extra Knights Companion of the Garter Knights of the Golden Fleece of Austria Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary 3 3 3 Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand Italian people of Polish descent Claimant Kings of Jerusalem Deaths by firearm in Italy Male murder victims Kings of Italy (1861–1946) Grand Masters of the Gold Medal of Military Valor Burials at the Pantheon, Rome Victor Emmanuel II of Italy